Just as people are upping their cleaning game because of COVID-19, a University of Saskatchewan researcher is raising a caution sign about cleaning surfaces with hydrogen-peroxide based disinfectants. Chemistry researcher Tara Kahan and her team have determined that the disinfectants have the potential to pollute the air and pose a health risk. The team found that mopping a floor with one of these commercially available cleaners raised the level of airborne hydrogen peroxide to more than 600 parts per billion. That’s about 60 per cent of the maximum level permitted for exposure over eight hours and 600 times the level naturally occurring in the air.

Kahan says, “Poor indoor air quality is associated with respiratory issues such as asthma.” The U.S. Centres for Disease Control says too much exposure to hydrogen peroxide could also lead to skin and eye irritation.

Kahan’s team also included researchers from Syracuse University, York University in Toronto, and the University of York in England. The results of their work were just published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology.

Kahan says the real risk is for people who get repeated exposure such as janitors and house cleaners. The impact on children and pets, who are physically closer to the disinfected surfaces, is not yet known. Kahan says more than 10 per cent of disinfectants approved by Health Canada that are deemed likely to be effective against SARS-CoV-2 use hydrogen peroxide as the active ingredient.

As an alternative, Kahan suggests using soap and water instead of a disinfectant. Soap and water are known to kill the virus that causes COVID-19.

You should also consider opening a window, turning on a range hood, or using your central air system because ventilation can dramatically reduce levels of pollutants circulating in the air and is one of the most effective methods of removing particles that can carry the virus.

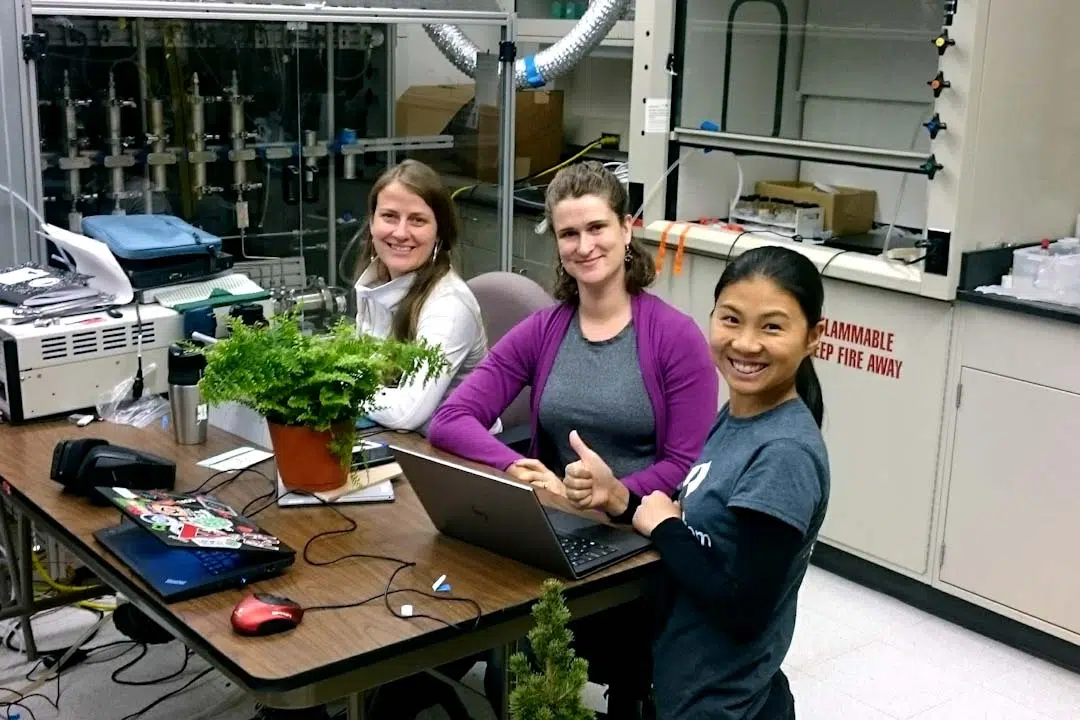

*Photo: Left to right, York University chemistry researcher Cora Young, USask Canada Research Chair Tara Kahan, Syracuse University post-doctoral fellow Shan Zhou measure air quality in a simulated room in a lab at Syracuse University in 2017. (Photo credit: Trevor VandenBoer)