Research being done by the Global Water Futures Observatory is revealing some worrisome water-related trends across the prairies.

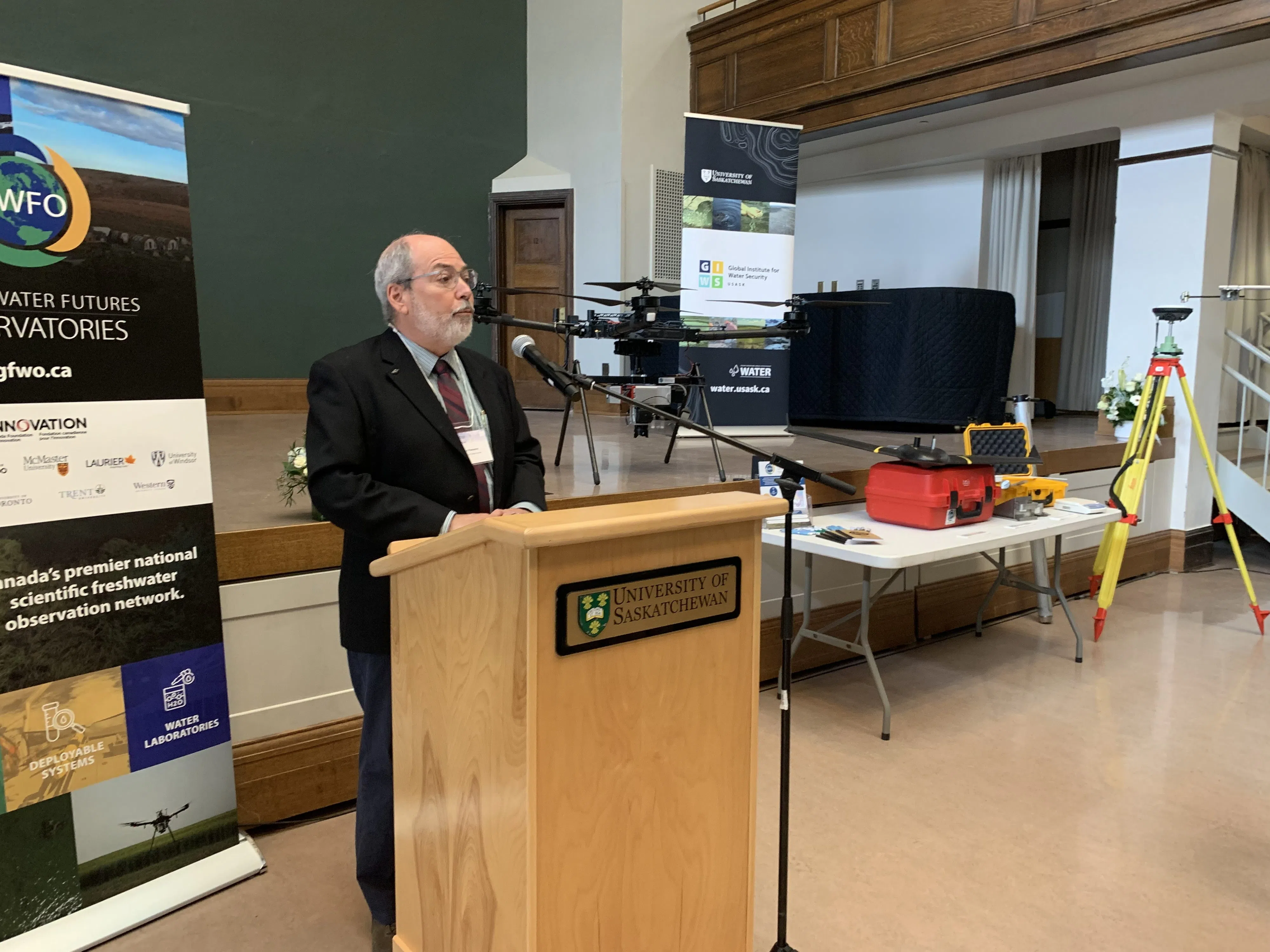

The GWFO, a nation-wide endeavor to monitor Canadian water resources and spearheaded by the University of Saskatchewan, was officially launched today.

Dr. John Pomeroy, Director of the Global Water Futures Programme, says severe floods and droughts, and the deterioration of water quality are the two most concerning trends being detected.

“Since the year 2000, we’ve had the largest, most intense floods and most serve droughts. Sometimes within a few years of each other, and sometimes in the same year but in different parts of the province,” Pomeroy explains.

On the topic of water quality, he adds that there has been a significant shift in water quality over the last few decades, affecting ground water, water in treatment plants, and remote water supplies used in small communities.

“In the early 1980s, the South Saskatchewan River upstream of town passed all the drinking water standards by dipping a cup in it. So that’s what we had, in living memory, but we don’t have it now. So, the deterioration of water quality is a very serious concern.”

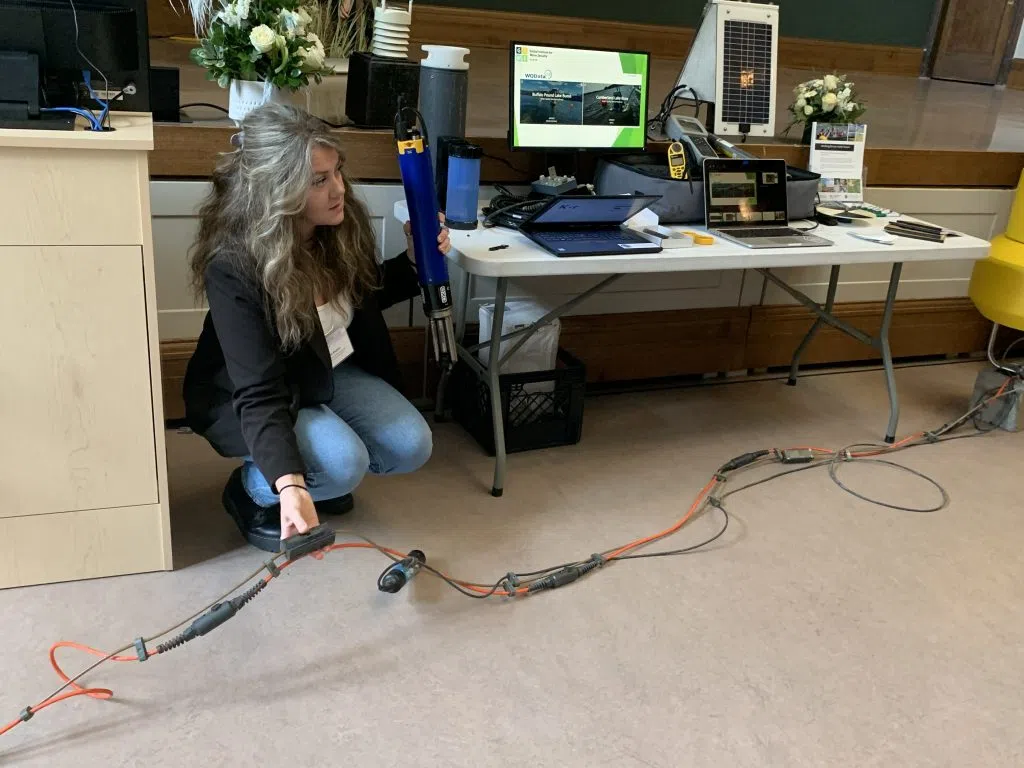

Using various technologies such as drones, weather stations, and buoys placed around the province, the GWFO has been collecting data on snowpack, water quality, precipitation, glacier melt, wind, and temperatures.

Pomeroy says Saskatchewan’s agriculture sector may soon have to adapt to the changing climate and weather patterns being detected in order to continue to thrive. Pomeroy has provided a forecast for the coming years and says, “Warmer, absolutely warmer, especially in summer and mid-winter, and less so in spring and fall. Overall, wetter, but…the increase in precipitation is mostly in the wintertime and in the spring, with summers becoming quite a bit drier.”

He says producers need to begin to think about planting crops that do well in these new circumstances, such as winter wheat.

He adds that a decrease of glacial runoff feeding the headwaters of the province’s rivers could impact water accessibility, as it already has in some places.

“The Saskatchewan River Delta around Cumberland House hit such low levels that muskrat populations plummeted (to) virtually unobtainable (levels). The community of Cumberland House had trouble accessing drinking water.”

He cites Leader, Saskatchewan as another community that is being impacted by the water crisis in Saskatchewan, as they also had difficulty accessing drinking water.

Pomeroy hopes the drought will end soon, but in the meantime, he says the data collected by the GWFO intends to help prepare us for future droughts ahead.

He explains the importance of the GWFO’s work, stating that the team collects data that governments do not, and data that is too difficult for citizens to obtain. For example, the organization has weather stations placed in the Rocky Mountains, Smart Buoys floating in Buffalo Pound and Cumberland lakes, and drones flying through the mountains capturing data. Pomeroy says government weather stations are placed at airports in large centres, so they aren’t able to collect information from the areas where snowpack is most important.

Madison Harasyn, Research Technician with USask Coldwater Laboratory in Canmore, AB

Katy Nugent, Research Technician with USask Global Institute for Water Security